Doing Something or Anything?

‘Go and do something’ is often cited as the founding mandate for The Salvation Army’s social and community work. Denominational history books report that, having been disturbed by swathes of rough sleepers throughout his ‘preaching patch,’ William Booth ordered his son, Bramwell to ‘go and do something.’ Bramwell initially protested, worrying that The Salvation Army would be drawn into trying to solve all the world’s social problems with indiscriminate charity. William reportedly replied, ‘Oh I don’t care about all that stuff. I’ve heard it all before. Go and do something.’

These four words capture TSA’s activist tendencies. Each day, tens of thousands of people will sleep in Salvation Army accommodation, receive healthcare in Salvation Army clinics and eat meals cooked in Salvation Army kitchens. In addition to professional and specialist social-service centres local Salvation Army corps around the globe find creative and innovative ways to serve their communities. Practical theologian Pete Ward observes, from the outside, that, ‘Few communities roll up their sleeves […] like the Sally Army. Even fewer […] maintain a vigorous commitment to an Evangelical gospel whilst being so deeply involved in working for the poor’. Ward observes that Salvationists understand their ‘doing something’ as intrinsically linked to their commitment to the gospel. Yet, is doing ‘anything’ that is charitable the ‘something’ that Booth had in mind?

Becoming culturally established

Unlike the Church of England, The Salvation Army is not ‘officially established’ as a state church, but we believe it has become ‘culturally established.’ A lot could be said about what ‘cultural establishment’ is, but in essence it is a status a body of people, organisation, charity or church can have in relation to the wider society. Being culturally established often means that an organisation needs or desires the financial and general support of wider society for its own survival. This is not always a bad thing. There are some wonderful things about Western society which the church should uphold and affirm, and it should partner with other groups to work towards these ends. We are worried, however, that over time The Salvation Army (in the West at least) has allowed itself to be aligned with the overarching narrative of Western societies in its desire to stay relevant and ‘do the most good,’ and has often fallen into the trap of wanting to do the ‘anything’ rather than the ‘something.’

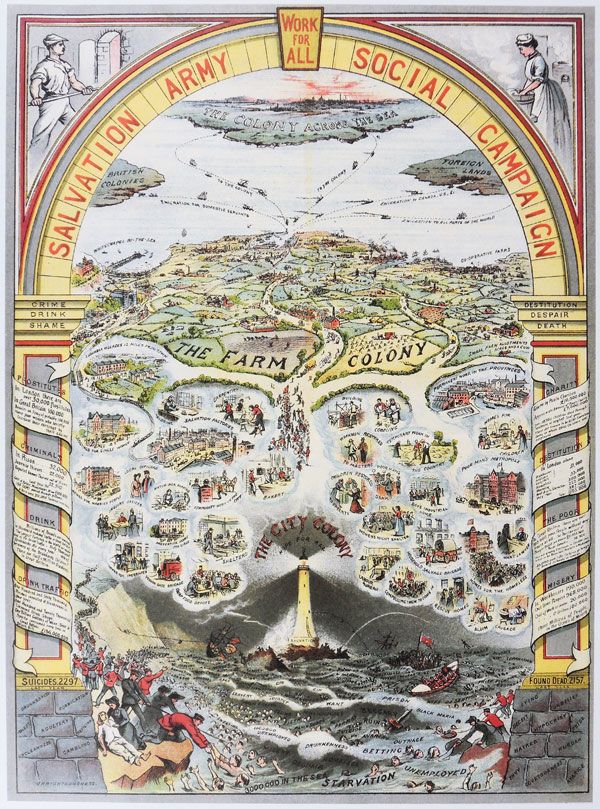

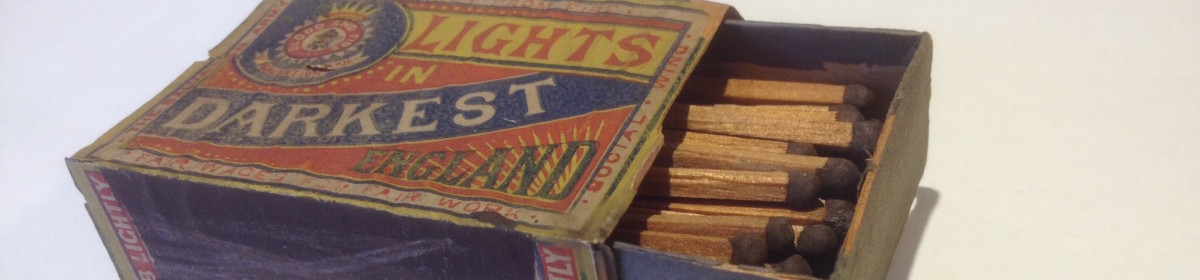

Whilst it would be untrue to suggest there was some ‘pure’ early phase of the Army, followed neatly by a more ‘compromised’ phase which stretches to today, a shift can be seen towards the end of the nineteenth century towards cultural establishment. Commissioner Ann Woodall notes how that, with the death of Catherine and the side-lining of George Scott Railton, William Booth allowed the Army’s social work to start taking precedence when it came to publicity, and more time was being spent on internal processes than outward mission. If bad publicity was the Army’s PR machine of its beginnings, something much more palatable emerged at the turn of the century and through the Darkest England scheme, Booth began to call upon the public to help the Army fulfil the aims which, broadly, the public already held.

A theological shift can also arguably be seen with the launch of the Darkest England scheme and book, with William moving away from a strong and explicit focus on Christ to an urgency about the task at hand. Lt-Col. Dean Pallant, for instance suggests that while Booth’s overall vision was in line with revivalist theology, ‘there are few explicit references to theological resources shaping [Booth’s] arguments’, and that he ‘fails to clearly articulate the role of faith in the transformation of the character of the individual. While he identifies “character change” as the first of the seven “essentials to success,” he does not specifically link it a Christological soteriology.’ Here, we see that parts of TSA start to be seen, by William Booth at least, as something of a social services agency.

Movement on this trajectory would accelerate in future decades as the Army’s popularity soared. Pamela Walker sums up what this shift entailed, where the early Christian Mission and Army had, ‘moved from being a sensational, revivalist sect at odds with the Church, police, and local governments to being a religious organization with a social service wing that was often the more prominent part and with strong ties to other Christian and state-run agencies.’ The situation in the UK became such that there were several Salvation Army ‘territories’ within the UK, with ‘Social’ and ‘Field’ Work having completely parallel chains of command, where rarely the twain would meet.

Why is this a problem theologically?

The danger faced by Christians when it comes to cultural establishment and wanting or needing general public support to keep going is that they often find themselves in a ceaseless crisis of legitimation where they find justification for their existence in terms of the wider social order. Nowhere is this more obvious in TSA than the generally agreed upon idea that good people ‘help others.’ You don’t need Jesus to tell you that, you can just watch Children in Need! This is also the source of our embarrassment whenever anyone is surprised when we tell them The Salvation Army is a church not just a charity.

This isn’t just a problem of TSA’s making though. Trying to make Christianity intelligible within the philosophical and sociological terms of Western liberalism has been disastrous, as Alasdair MacIntyre comments – we end up giving atheists less and less in which to disbelieve. We turn Christianity into one lifestyle choice among many and stop trying to be a concrete, embodied alternative to all forms of life which do not give glory to the God revealed in Jesus Christ. It is but a short step from this to downplaying the importance of distinctive and particular Christian worship as a key part of following the ways of Jesus. This is particularly true when it comes to public relations, when we do not want to discourage potential donors by muddying the waters with much that might be particular to Christians.

We’re not suggesting that the church needs to become triumphalist, arrogant or aloof within society, nor that we need to become some kind of ‘Holy Huddle’; a super spiritual agency planted firmly atop a moral high-ground. Many Christians, indeed many Salvationists, would rightly baulk at this idea. But you can go too far the other way too – downplaying any distinctiveness following the God revealed in Jesus might make. The ways of Jesus are particular. They’re not a vague ‘anything’ that is a nice, palatable value. They’re grounded in an objective story: God’s story for the world, centring on the sending of his Son, Jesus. This isn’t just an anything: it’s a something.

Keeping the Something: TSA as a Movement

The question of identity for The Salvation Army has sometimes been framed as ‘are we a church or movement?’ When Salvationists feel uncomfortable at being called ‘a church’, the uncomfortableness they’re often expressing is that they don’t want to be seen as a ‘pious party’ of religious people, caught up in maintaining its own existence. They want to be seen as missionary; moving out into the world, dynamically proclaiming and demonstrating the gospel in the broadest sense, engaging with the ‘whosoever’. This is the kind of movement that is in Salvationist DNA but really, it’s what the church was always meant to be.

Someone that we could possibly learn from in this regard is the legendary twentieth century missionary-theologian: Lesslie Newbigin. Newbigin wasn’t a Salvationist (he was a Presbyterian who became a bishop in South India and ended up as the moderator of the United Reformed Church in the UK) but we think he’d have been comfortable in our ranks. He, rightly, understands the church as being, by its nature, a missionary movement gathering momentum towards the glorious future God has promised. Newbigin describes the church as a movement which is the ‘sign, foretaste and instrument’ of the reign of the Kingdom of God. The church, as a sign, points to the redemptive reign of God in history. As a forestate, it is an actual down-payment that the eschatological Kingdom of God has already begun. As an instrument, the church is the means by which God’s redemption bears on every aspect of human life. It rubs up against the surrounding culture. It creates tensions with the world that is around us. Yet, it’s powerful and it’s exciting. It’s the ’something’ TSA is called to.

Newbigin’s work is, for Salvationists, a treasure-chest of golden insights that speak into our context. He worked in social-justice work in Glasgow, before training for formal ministry and then spending many of his formative years in India. Returning to the UK in the late 1970’s he was dismayed at the rapid cultural changes he observed in Britain in the 30 years he’d been away. He saw England as a ‘pagan society’ and was worried that the church was having something of an identity crisis, lacking the know-how to engage with an increasingly hostile culture. His solutions?

“I am suggesting that the only answer, the only hermeneutic of the gospel, is a congregation of men and women who believe it and live by it”

“When the message of the Kingdom is divorced from the person of Jesus, it becomes a programme or ideology, but not a gospel”.

Newbigin is suggesting that we make the gospel intelligible by our actions, but that these actions only really make sense in the light of a community of people, a band of warriors, who have been shaped and formed by the gospel story in a way that it spills out into their locality.

When you put it like this, any conception of ‘the something’ TSA is called to do as ‘just doing nice things’ seems like a remarkably puny vision for all that Salvationism is called by God to be. Having encountered God’s kingdom for ourselves, having been assured of our salvation and sanctification, we’re called to march out into the world, into our communities, into our neighbourhoods with our sleeves rolled up as an overflow of God’s boundless salvation and his deep ocean of love in our lives. Nothing less captures the mission of TSA. We aren’t just the YMCA with hymns.

Recommendations

What can or should be done about this, then? We do not claim to have all the answers and are inspired by the practical responses of so many of our brothers and sisters within the Army resisting the forces of ‘vague charity.’ Remembering who we are, like Simba, however, will need significant and radical changes, we believe, and we suggest five recommendations below which might help on the journey to re-focus our eyes upon Jesus as a movement once again:

1) Make the main thing the main thing

If the only hermeneutic of the gospel is a congregation that believes it, the key question that should guide all decision making from a local corps level right to senior leadership is this: ‘what will build up the worshipping community of Salvationists to witness to the gospel in word & deed?’ This question should also be applied to our current work, and if it is judged that an aspect of our work has little or nothing to do with building up worshipping Salvationist communities for this task, then we should seriously consider its continuance.

2) Remind ourselves of a time when we didn’t mind being unpopular

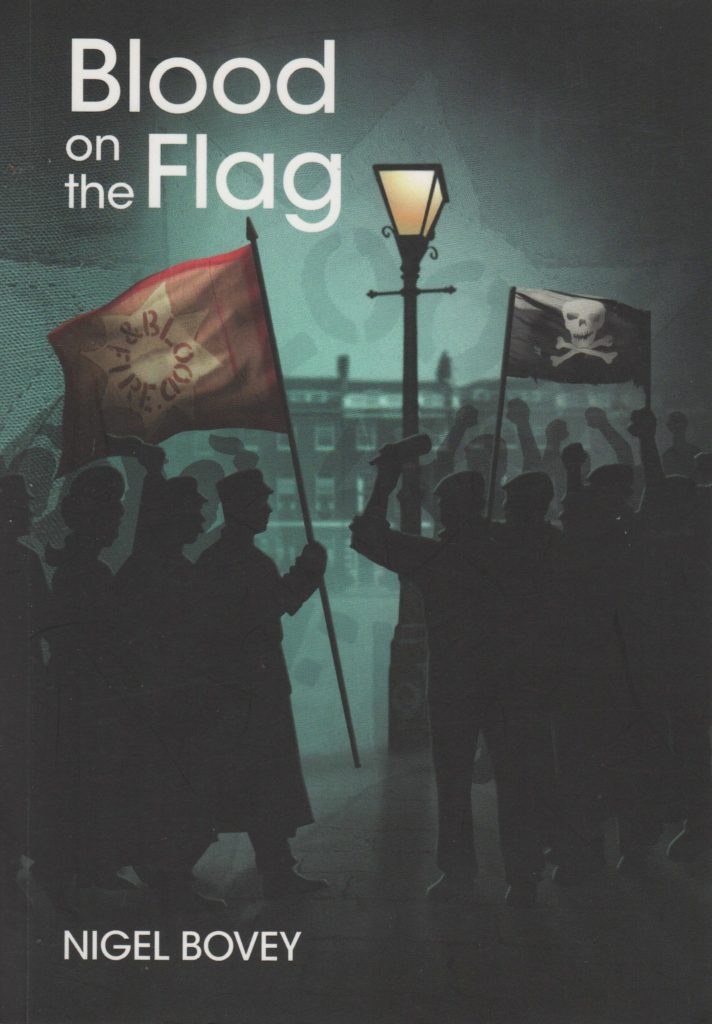

If we are right, ridicule and scorn should not be sought for their own sakes but will be an inevitable consequence of faithfulness to the gospel. Jesus and the New Testament writers seem to suggest a degree of rejection or persecution is inevitable (John 15.20, 1 Pet. 4.12, 2 Tim. 3.12, 1 John 3.13). Nigel Bovey’s book Blood on the Flag is a well-documented account of the Army’s period of oppression by the Skeleton Army in the late 1800s. This is a great example of the Army not being afraid of being hated and rejected for assuming Jesus’ ways will be different from much of the world.

3) Re-configuring officership

An inevitable consequence of the above points would be a reduction in income. We are not naïve about this. This would be a shame in many ways, but if it helps the Army be more faithful to the particular narrative of the gospel, it would be worth it. The challenge then, of course, would be how to fund corps and social service centres.

While not doing away with the calling of officership as a distinct aspect of ministry beyond soldiership/adherency, might officers be encouraged to consider more tent-making endeavours (e.g. part-time work) to lessen the burden especially on small corps to raise funds to pay for the cost of officers? We need to find new ways of thinking about, and responding to, these old problems.

4) Keep our Mission Worshipful

Salvationists have a heritage of not limiting God’s activity to certain places or times; we’ve expected to find Christ whilst sat in disused skating rinks and when kneeling at drums in the street. We’ve encountered him whilst serving in shelters and soup-kitchens. As Newbigin reminds us, though, we need to ensure that the ‘somethings’ we do aren’t divorced from the ’someone’ who calls and sustains us. The Salvation Army’s missional activities should lead people (especially those facilitating the activity!) to worship God in deeper and more explicit ways. That’s one of the things that distinguishes Salvationist activity from vague charity.

5) Keep our Worship Missional.

As Salvationists meet for worship, we gather to give God glory. As we do, we encounter a missional God who is reconciling the whole world to himself. It’s big stuff! Our Worship isn’t a social club meeting, It’s not entertainment. It helps us to encounter a God who, having met, we can’t help but follow into the world. As the Cliftons and the Cokes remind us in their report Marching towards Justice, Salvationists should ‘take every opportunity to preach boldly the saving power of Jesus Christ and the coming Kingdom of God, by raising the flags, marching the bands and singing the songs of justice out in the public square’.

We would love to hear what you think about what we have written. Please do respond in the comments section or on social media. We desperately need mutually challenging and encouraging debate and discussion if we are the face the significant challenges facing us as an Army.

Hi, thanks for your hard work writing this! I’m keen to understand what is meant by ‘If the only hermeneutic of the gospel is a congregation that believes it…’. Is it that the only lens of interpretation here should be people that believe the gospel, or maybe that the gospel should be interpreted in community rather than by one person? Or something else altogether?

Hi Hannah- Callum here,

I think what Newbigin means by, ‘I am suggesting that the only answer, the only hermeneutic of the gospel, is a congregation of men and women who believe it and live by it’ (which is what we were quoting in the first point for action) is that the only thing that really makes sense of the Gospel, the only way to make it intelligible, the only interpretation of the Gospel that make sense, is when it is embodied into the lives of a community. He’s saying that ‘you don’t just make the Gospel intelligible by explaining it in intellectual terms…it only makes sense when its transformative power is lived out by a community’. Newbigin is super keen to push back against any individualistic interpretation too (as you hint towards): he says that it’s as a whole cross-cultural communal understandings are put together that you get something more resembling the truth!

I think the key is that the Gospel isn’t just something that’s believed ‘in our heads’ or intellectually: its something that we live within. The key for us is that the things that the Church does, should be done within the context of the incredible story that is this thing called ‘The gospel’ Does that make sense?!!

Thank you for an excellent article and a lot of food for thought. Great recommendations of making the main thing the main thing, mission worshipful and worship missional.

In re-configuring officership, I would suggest that before advocating tent-making the ‘expense’ of divisional/territorial levels need to be looked at. The issue of tithing needs to be more strongly addressed in corps. And for some corps, making the main thing the main thing would raise the question of whether they need their building or could they function by renting space instead?

Tent-making also feels like it risks devaluing the calling/need of officers even more than it already has been, or maybe I’m misunderstanding the point?

Hi George,

Thanks for this – some challenging thoughts. Great point about tithing – I think that would be natural outworking of keeping the main thing (the Gospel…) the main thing. Communities formed by the Gospel are naturally generous. There are other churches I know, with no access to central funding, with similar demographics to corps I know who have much bigger budgets…simply because their congregations give more money to their Churches. This is another consequence of ‘Cultural Establishment’: The surrounding culture love the work an organisation does, and so support it, which eases some of the pressure on the organisation to be internally self sufficient.

The point about tent-making seems to be one that’s garnered a lot of traction, particularly on Facebook and has really split opinion! Some shouted unequivocal ‘Amens’, others were highly cautious. Sam and I feel slightly different to each other about this point. I think, though, that point needs to kept in the context of the whole blog. We’re saying that if we try to move away from being ‘Culturally Established’ then there’ll be financial implications. One solution around that could be tent-making- which makes things cheaper! I agree with lots of your concerns though- I think part of the problem here too is that we need to make sure that we consistently mobilise non-officer leaders too, into real leadership within their corps. Soldiers are really, by their covenant, already, tent-maker officers! The point about tent making really comes under the idea of ‘we need to have new thinking for new problems’ and we should, as you say, be able to ask big questions and dream up big possibilities in the present climate. I think, as you also say, looking at other costs elsewhere would also be vital.

The other thing is- as has been made elsewhere (and I wish I’d thought of it myself!) is that being ‘unpopular’ or non-culturally established might not have any financial implications for the Army- as it didn’t for the early SA either.

Thanks for your reply Callum. You’re right that tithing would come out of keeping the main thing the main thing…I hadn’t thought of it like that!

Where you say ‘soldiers are really, by their covenant, already, tent-maker officers’, could you expand on that a little more? Is there any distinctive then, other than performing ceremonial aspects, to someone being an SA officer? Envoys/Pioneers do the same roles as corps officers and there are so many different avenues of service in the SA other than officership. Is the distinctive solely down to a calling or availability? I’m not sure if I’m making sense in saying this(!) as I’m not saying an officer is more important than anyone else, just trying to work out the distinctive.

Thanks again for the article and discussion arising, it’s been great to reflect on this. Blessings to you in your ministry.

Hi George,

I think you’re getting at the heart of the issue there! (IMO). What actually IS an officer? (And what makes that distinct from other things). For me, there’s two strands to the question: the theological and the functional. Theologically, as you say, I think the only real difference is ‘availability’. That’s both availability to the Army (i.e. I’ll go where my leaders say and do what they say!) but also availability to the cause: (i.e. the officer’s covenant says that officers make ‘soul winning’ the first/primary purpose of their lives). Officer’s are freed from the need to take other employment/housing etc., in the main, in order to make this availability happen. I’m not sure I’ve been able to square the difference between an officer and a soldier (who make SIGNIFICANT commitments to the Army and God in their Articles of War!) any other way than this, theologically… Did you have anything else in mind?!

There are, then, of course though I accept the functional differences in practice. I think many of these are ‘just what happens around here’ rather than being theological decisions though. In most corps, it will be the officers who mostly lead worship and preach, conduct ceremonies, chair the leadership team, manage the budget (overall) and take responsibility for leading the corps. Mostly, an officer assumes these functions in the main. But, theologically (and according to O&R…) there isn’t a barrier to stopping a soldier doing any of those things (except, as something of an anomaly, in the U.K. weddings…which are the only thing only an officer can do – even envoys and pioneers can’t do weddings).

Therefore if the only thing that makes soldiers and officers different, theologically, is their availability, then soldiers are really “tentmakers”- in as much as they’re engaged in paid employment in order to resource the ‘Salvation War’ (their articles of war already committing them to give as much of their money and time as possible to the corps!). I completely concede, though, the ‘theory’ and ‘practice’ of this might be two different things all together though.

It’s the availability thing, too, (for me) that also helps us understand how we make sense of officers doing things like finance, or trade, or working in a social centre as an administrator… Being an officer isn’t just about the “being a vicar/pastor/priest” type jobs it’s ultimately about availability.

Good to chat about it!

Love this call to rediscover our identity. Would strongly echo the thoughts around our worship. Some years ago there was some material produced by Spiritual life commission chaired by Bob Street. I remember one line about a call to worship involving a vital encounter with the living Christ in every meeting. All these years on do we again need to remind our people about that possibility and raising their level if expectancy whether engaging in worship in person or online. With the number of employees now far outnumbering the numbers of officers and possibly the number of soldiers (not sure) is it time to get smaller and do less but do it with radical disciples who know Christ and who believe in the transforming power of the gospel rather than rely on the good work done by thousands for whom The Salvation Army is just the employer they work for, who may be in sympathy with our aims but who do not profess to know Christ.

God can and will use whoever He wants but I just think something wonderful happens when the kingdom of God at work in a persons life spills out for others to taste and see. It can be contagious. Thanks again for great blog

I feel the salvation army does a good job in a capitalist country. The church always stands alone because it is seen as “religion,” indoctrinating the masses. I don’t think that but friends have told me that. It’s also hard to even consider Christianity when you are socialised as a child, youngster and adult to take drugs, steal, be all for yourself and get as much money and things as you can and help yourself and not your community. I dont think these things but they’re prevelant in my local community.

So I think it’s education. I think young children need to be educated about church and then they don’t get indoctrinated they get information which leads to choice. Church is fantastic for those looking for God or who already believe but ive met 3 Christians on my travels and I’m 52 that I didn’t meet in church. That’s why community ministry is so important. I hope that doesn’t change because Christians and the SA and Baptist church provide a home for those that rebelled. The aethiests that protest and those like me who arent sure and those hundreds that have never been interested or introduced can go to God and repent and recieve help. But if the church isn’t strong on scripture, worship, faith and gods commandments the rebels and the ignorant have nothing to come to.

The salvation army officer and soldiers are the backbone of the church and people to be looked to as examples and mentors. The Christians guide the rest of the people they meet.

The church is like a family home were God lives and that is to be respected.

I don’t think officers should work. The congregation need to be encouraged to volunteer for roles in the church. I think it’s commitment and giving up personal time that’s hard. I fall down on commitment myself and I wouldn’t judge others but it is a problem. Some form of outreach to teenagers, prostitutes, criminals, homeless etc.. is good news but getting to the attitudes of the general public is a massive challenge. Theres racism, class divide and ageism and other divides in society. Marriage is not popular and blended and dysfunctional families are everywhere. The Salvation army stand apart because they take gods word out to everyone and are not elitist.

God is good as my dad says. The Salvation Army has to come to people now through technology which is a challenge. Tolerance for people who are not part of the church and education is the way forward to me as well as helping practically.

Thanks for your blog. I didn’t understand it all but I think its great that young families are keeping the church alive.

Moderator: I submitted a similar post yesterday but it has not appeared so posting again. If previous post is waiting to be approved – then delete this.

Thank you for an excellent article with a lot of food for thought. Great recommendations of making the main thing the main thing, keep mission worshipful and keep worship missional.

In re-configuring officership, I would suggest before advocating tent-making, there needs to be a look at the ‘expense’ of the divisional / territorial level. The issue of tithing needs to be better addressed in corps (how often is it spoken about?) And in making the main thing the main thing, it could be that some corps find that they do not need their own building to do this, perhaps rent space when needed instead?

Tent-making risks devaluing officership even more than it already has been, there are so many alternative routes offered already within Salvation Army circles. The availability of the pastor/officer which if employed elsewhere part-time, may not be possible in the same way. I think we potentially even water down the seriousness of the mission which you’re suggesting, because we don’t have the need of people to be fully available in the sense of how an officer is. Or am I misunderstanding the point you are making?

Fantastic article – thank you.

This is offered for reflection more than anything else.

If our life “is hidden with Christ in God” (Col 3:3), the visible expression of our actions flow from that hidden life. Our outward life comes from our inward life. We ‘go’ (as in ‘go and do something’) from a place that is hidden. We ‘come from’ that places we go. It is the place where our identity is graciously gifted to us by a loving God who delights to call us beloved children.

It seems to me important to always keep that in mind.

The relationship between action and contemplation is subtle and nuanced … and our activity oriented movement (or church!) can be caught in the trap of a dualism that sees these as separate instead of one. The use of the word ‘social’, for example, may not be any less authentic as ‘the gospel here and now’ merely because it is played out in the public square and financially supported by the public. It flows from that life hid with Christ in God. I have been frequently encouraged and inspired as I listen to our teams in those social services settings (and conferences) revelling that the gospel of Jesus is transforming lives … every day it seems in some settings. I guess that one could argue that every expression of what the Army is doing in the territory could be a powerful witness to the Kingdom of God here and now, as an expression of ‘God with us’. It is only when that life hidden with Christ in God is disconnected that social action can be distorted … but that could be said of many things in the Army – fellowship, generational ministries, music, administration, systems and rules etc. in fact any aspect of our life that is played out in the outer world.

Finding the balance between action and contemplation, worship and social action, things hidden and things visible will always a challenge to the egoistic self both individually and corporately.

Maybe being popular or unpopular isn’t the point … perhaps the point is letting go of our need to be popular (or unpopular) and dying to any sense that our image in the public square matters too much … and allow our true and hidden identity in Christ be enough!

Thanks Alan! I think you’re placed more than most to speak into this.

I was really keen to avoid implications that pitted “Corps” vs “Social” because I agree with you: it feels dualistic and fairly arbitrary. I think when you talk about the ‘many things in the Army’ you hit the nail on the head too: my point (I can’t speak for Sam!) is that when any activity is divorced from the life hidden with Christ it becomes ‘distorted’ and loses some its meaning. I think lots of what we spoke about applies to Corps life too.

The balance between the two elements is where I think we need to be thinking: Contemplation/Action, Worship/Mission, Visible/Invisible, Piety/Charity (Wesley’s words!), whatever you call them… For me, that’s where the ‘Worshipful Mission/Missional Worship’ idea is really useful because both of these concepts feed into each other. Our ‘Hidden life’ effects our public action, but our public action should also lead us back into this hidden life. In a sense we can’t help but ‘go public’ after a hidden encounter with the missionary God. If we don’t ‘go public’ then our corps are really just a social club with a few hymns. Similarly, as we fight for justice and be alongside the marginalised, we’re drawn back into an encounter with the missionary God.

In terms of the being unpopular idea- I agree completely too. It’s not about trying to be unpopular (or popular…) but about being faithful to our identity.

What I’d be interested to hear your thoughts on further is what happens to ‘social action’ when it is divorced from the ‘inner life’. If the Rotary Club house someone, is that the same as TSA? Is an action done without the connection to the inner life the same as an action which flows from this place? I think the use of the word ‘distort’ has helped me today to understand that a bit better… of course, a homeless person housed is a ‘Kingdom Action’ in a sense and is really important..but maybe it’s meaning gets distorted divorced from the hidden life?!

Thanks for your kind and helpful reply Callum – you guys are really doing a great job with this – huge respect to you!

If an ‘immediate’ social or physical human need is met (by anyone), personally I give thanks! God loves everyone – therefore transforming and improving the circumstances of people is always a good thing whether it involves providing a home, a meal or rescuing them from abusive and corrupt situations … or whatever. However, we want to so much more for people and for us this is not the whole story, but perhaps a useful starting place. (we would do it anyway because we love people!)

The mission of God connects meeting ‘immediate’ (often urgent) need, with what I would call a persons ‘ultimate’ need, which is receiving life in Christ … the whole gospel to the whole person (holistic mission) which we call salvation (the life and ministry of Jesus clearly demonstrates this). In the meeting of immediate needs, we can develop a credible platform that can facilitate sharing the gospel – most effectively done when we are asked why we do what we do. For me, this is why it is vital that corps must serve in/with their local communities … I believe that for the Army, the future of mission lies there as many are discovering through new and innovative approaches to mission – such as our work with refugees, food banks, debt advice, kids clubs and so on. I would also advocate that our social centres be recognised as local expressions of church … there is a good deal of work going on to develop this (Recovery Church example). What an incredible opportunity we have!

Thanks Alan…I’m not how great a job we’re doing but we’ve had some really thought provoking responses!

This reminds me of what Eva Burrows once said, ‘If you take a homeless man (sic) to a hostel, they’re a housed man. If you take an alcoholic man to rehab, they’re a sober man. If you take a man to Jesus, he’s a transformed man!’. I agree: “just” being charitable is selling people short of the fullness of what the Gospel offers. The link between the ‘Immediate’ and ‘ultimate’ need is key to TSA I think (“Nobody ever got saved on an empty stomach” etc!)

I’m also in agreement about not calling social centres, social centres! In Australia every corps, centre, charity shop is now called a ‘Mission Expression’. What a title to live up to. I think social centres and programmes are sometimes underestimated by those who haven’t encountered them…

I think the theme I’d be keen to also emphasise, though, is the ‘back loop’ (for want of a better word). Absolutely, as you say, engaging in mission gives salvationists a platform to explain to those they’re with about ‘the reason for the hope they have’. If this is the ‘whole picture’ though, it’s in danger of being a bit (dare I say?) manipulative (i.e. I’ll give you food so I can give you the gospel, which is what I really want to give you!). I don’t think that’s what you’ve said: because the ‘other element’ of the picture is also that giving someone food (for e.g.) is also as you say we do it because we love people and it’s a good, kingdom thing to see awful situations transformed. I think, though, these two things alone aren’t the whole picture either: they just leave us oscillating between traditionally the “conservative” idea of using any means as a way of eventually being able to preach the gospel, or the traditionally “liberal” idea of being nice people, building the kingdom without needing a faith element. For me, it’s that as Salvationists (and Christians…) engage in the world, as they give food to someone (in this e.g.) they’re aware that they’re giving food to Christ and in that sense they are ministered too also (e.g. Matt 25). We don’t only engage in mission to ‘give’ but to ‘receive’. For my own part, working with refugees has been a really powerful example of that. We set out to transform the lives of a refugee family, and found (and I don’t mean to sound corny!) that our lives have been completely transformed. Perhaps the way that we maintain the relationship between the ‘hidden life’ and ‘public action’ is in those three elements: kingdom actions, transformation in the life of others, and transformation in our own lives… I agree, huge potential!

Well expressed Callum and I agree wholeheartedly.

Manipulating people is always abhorrent – sharing of the gospel in words is more often best done in answer to questions or enquiry in my view. Evangelism is primarily listening – speaking comes later (Wesley’s quote on ‘sometimes using words’ comes to mind).

I love the Sam Wells thinking on ‘being with’ … which suggests that we are as much (or more!) in need of transformation as anyone else. A foundation discipleship reality is a willingness to lay down our lives (and ego) so that others get to pick up theirs.

Every centre an expression of mission – great!