By Saul D. Alinsky, taken f rom the introduction to: Alinsky, S. D. (1970). John L. Lewis, an unauthorized biography. New York, Vintage Books. Pages ix-xiv

rom the introduction to: Alinsky, S. D. (1970). John L. Lewis, an unauthorized biography. New York, Vintage Books. Pages ix-xiv

This is the story of a man, of a revolution and how he led it.

It is relevant to our own revolutionary times. All great social crises turn on certain common concepts. One is that progress occurs only in response to threats, and reconciliation only results when one side gets the power and the other side gets reconciled to it. Another is that the power of organised people is required to defeat the power of the establishment and its money. A third is that effective tactics means going outside the experience of the enemy, and a fourth is that all issues must be polarised. These and other revolutionary concepts hold true through all the revolutions of man, no matter in what place or time.

Today the greatest technological revolution in history finds us in a computerised, cybernetic, nuclear-powered, mass-media jet age, where we are inundated with information and know more about the happenings in the world around us, from Cambodia to Biafra, and yet we know less. The massive deluge of information and the onrush and changing character of problems give us no time to digest and think. Thus it is especially important today to remember, as I have pointed out elsewhere, that with rare exceptions revolutionaries arise from the middle class, whose members, having a certain economic security, have time to think and develop. Today most people in western society have more time to look around, to be aware of other things and how they are related to their personal lives. Mass media have smashed their private worlds with “Look! Pollution is here and killing you!” “Look! Overpopulation is destroying the world!” Look! We can’t even get out of Vietnam and we’re getting in somewhere else!” “Look! Inflation! Race Riots! Campus Riots! Police Pigs! Law and Order! The Bomb! Look! Look!”

Everything is so fractured, ever moving and changing, that it makes a kaleidoscope look static. To many the world is hellbent for hell in a hundred different ways.

But let us go back to “the good old days,” three decades ago, to the time of this story. The early 1930’s were days of great violence. Negroes (they are called Blacks today – but only white racists called them blacks then) were being lynched regularly in the South and rigidly segregated in the North by restrictive covenants in real estate. White civil rights agitators and labor organisers were being tarred, feathered and castrated. The Ku Klux Klan claimed in its membership nearly every southern political leader. Our corporate establishment was even more arrogant, proud and all-powerful, and profound believers in the American way of a free competitive society, free to exploit, free to crush any obstacle which blocks the road to Mammon. Labor unions were stated as subversive. Workers who even mentioned them were fired and blacklisted by industry. None of America’s corporations, from steel to oil, from auto to rubber to meatpacking and everywhere else, had a labor union. The vast bulk of workers was unskilled, and were hired and fired with brutal callousness. They worked as dehumanised, animated accessories to the ever-moving assembly line. Relatively few were specially skilled. The elite of the blue-collar working class had their craft unions in the American Federation of Labour, but they differed from the corporations only in that they regretted the plight of the vast mass of the unorganised exploited workers but generally the country was all right as long as they got theirs.

Profit and patriotism went together in that order. There were no gouging stores in the ghettoes of the poor, only company-owned stores in company towns which robbed you outrageously and didn’t permit competition. There were no deteriorated inner cities, only stinking slums across the tracks. Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle accurately described the living and worked conditions of the times.

In foreign affairs our government was pursuing an even-handed policy of great foresight. It knew then that Russian Communism was doomed, certain that the Russian people would at any moment rise to overthrow these bloody-handed revolutionists. This we balance off with a paranoid fear of world-wide creeping Communism. Our attorney general had a very energetic young director named J. Edgar Hoover, head of a young bustling organisation called the F.B.I., who was systematically hounding, raiding and arresting all suspected agitators, subversives and reds. With this, Congress conceived a new committee called the House Un-American Affairs Committee, which was hysterically unearthing Communist revolutionary plots everywhere. There republic was in great danger!

Meanwhile we denounced the Japanese invasion of “Free” Manchuria but sold Japan the scrap iron with which to make war. We denounced Franco’s fascist invasion – armed by Hitler’s Panzer divisions, Nazi strike-dive bombers and Mussolini’s soldiers – against the democratic republic of Spain and at the same time slapped an arms embargo on the republican government of Spain. For the first time in history a legitimate government was denied the right to purchase arms for its own defence. We sold the idea of a League of Nations, the United Nations of that time, and then wouldn’t join it. Very different from today, when we belong to the United Nations but pay as much attention to it as we did to the old League. Wars, tensions, resistance movements, rebellions against colonialism were all over the globe. We brought in Selective Service; strange new things sprouted, like passive resistance, and a skinny little revolutionary with a loincloth and spinning wheel showed up. Many didn’t like him, but felt better when he rejoined the human are by banning non-violence and forcibly invaded Kashmir. Yes, those were the days, my friend, sane, rational, stable and secure, very different from the frenetic mad violence of today.

We had no problem of pollution then. People were born and grew up in the overpowering stench and crapped-up air in meat-packing sections, but then you got so used to it that fresh air smelled funny and sick, only Communist agitators complained about the stink. All the workers in steel and coal-mining towns lived in an atmosphere of black-tray dust and soot but we had no words like pollution or environmental violence. They were different times. The big demand then, with crime rampant and bloody strikers, was for “Law and Order.” Those were the “good old days.”

Then it happened. Suddenly the bottom dropped out. The world they knew closed around them, their savings lost in closed banks, their jobs lost in closed factories; homes and farms were lost as mortgages and rent collection closed in; sharecroppers were forced off their farms. The great depression had begun. Everything went cold and lifeless, from smoke stacks to steeples. America tried to close its eyes and say, “This isn’t for real -it’s a nightmare and we will all wake up back in our jobs, homes, Sunday picnics, two chickens in every pot and two cars in every garage an all the other goodies.” But it didn’t work.

Then we tried to laugh and sing our way out, with Will Rogers leading the way and “Brother, can you spare a dime?” – but it began to hurt too much to laugh. we the turned to the every human hope, “It can’t last much longer.” We were reassured by rhetoric from the White House that relief was just sixty days away, and our churches solemnly sermonised that “This, too, shall pass away,” but it didn’t; it got worse. We began seeing things we thought couldn’t happen.

Veterans of the American army, encamped along the Potomac, petitioning for sustenance in the form of a bonus, were driven out by the bayonets of the American army. The months went by and despair set in; evictions began for non-payment of rent; youngsters left home and took to the road, either so that there would be one less mouth to feed or just to get away from what had been cheerful bustling homes but had turned into funeral parlours. Maybe “over the rainbow” there would be something better, or at least something.

Yet something was stirring in the land – a common mystery began to break down the barriers between people, began to erode the good old American ways of rugged individualism, the survival of the fittest, sanctimonious charity, “The poor we shall always have with us. After all, a certain number of people are too stupid to make it, so they’re poor.” But now that most of us were poor – were we all stupid and incompetent? We knew this couldn’t be true. All of our guide points, our values, our way of life had disintegrated and we were lost and dangling in a cold emptiness. In this void we reached out for something, anything to hand on to, and found each other. We found we needed each other. Unbelievably in this great crisis it came as a revelation that people could care about us and that we had it in us to care for others. new values began to creep in. Our literature began citing John Donne’s “No man is an island, entire of itself…any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involve din mankind; and therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee.” And Steinbeck’s Okies suffered through The Grapes of Wrath. A common tragedy shattered our private worlds and we found we had much in common with our fellow man. There was a warmth in our getting together and getting out of the uncaring cold. It was a wondrous experience.

People caring for each other began to fight the evictions of others; as fast as the sheriff moved the furniture into the streets, the neighbours carried it back and then defied the police. People organised for more relief; they demand jobs, and if industry couldn’t provide them, then the government must.

The fact that many things that were talked about were no longer in the traditions of the past “American way” was just too bad. To hell with the past. The past was dead. If this meant revolution – so be it. With considerable skepticism they elected, as the lesser of two evils, Franklin D. Roosevelt and his New Deal. Desperation gave some wishful meaning to rhetoric such as “We have nothing to fear but fear itself.” F.D.R. got across through radio “Fireside Chats,” through manner, words and smile that he cared, and most important, he began to be bitterly attacked by the establishment and its press. Cartoons showed a group of the rich in evening dress outside a swanky city club, calling up to friends standing by in an open window. “Come along, we’re on our way to the trans-Lux to hiss Roosevelt.” New Deal Democrats were being elected everywhere, and soon the only Republicans that could be found came from under the rocks of Maine and Vermont. Massive government programs were in the air. Government agencies were popping up every other week and being identified by their letters. W.P.A – T.V.A. – S.E.C. – N.Y.A. – and so through the alphabet.

Hope began to come, and hope begat anger, anger against the system, way of life, the establishment, call it what you will, which was held responsible for the economic disaster.

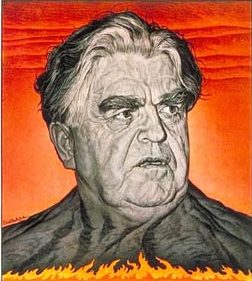

The suffering began to coagulate the unskilled unemployed poor, the unemployed artists like Ben Shahn, writers like Richard Wright and radicalised middle-class college students into a militant working class. Into all this came a man, John Lewellyn Lewis, to organise an economic revolution: to fight the entire corporate structure of the nation; occasionally with his own government, with the organised labour union establishment. Rarely has anyone been so reviled by the nation’s press. To the establishment he was Satan reincarnate. To the people he was Jefferson, Jackson, Lincoln, Lenin, Garibaldi and Napoleon rolled into one. Every radical of every suasion flocked to the banner of John L. Lewis. “A man’s right to his job transcends the right of private property.” “We are the workers – they are the enemy.” It was war, and the Chicago police maintained their historic role, shot down peaceful pickets, shot them in the back on the infamous Memorial Day Massacre – but then you must remember those were the days of violence. Many of John L. Lewi s’ tactics were brilliant in conception and execution. There are important lessons here for today’s battles; important warnings of mistakes not to be repeated. This is the story of John L. Lewis.

s’ tactics were brilliant in conception and execution. There are important lessons here for today’s battles; important warnings of mistakes not to be repeated. This is the story of John L. Lewis.

S.D.A

1970